Module 2: How GIS works

2.4 Differentiation of GIS

|

Cartographic images, interactive maps, web GIS or desktop GIS are common forms of presentation and tools that have become indispensable in public media, specialised applications and research and development. However, due to their different functional scope, the respective applications are used in different areas in a user-specific and practice-orientated manner. For example, environmental information systems, land cadastres and network information systems are usually geoinformation systems that are tailored to specific requirements and are sometimes based on different IT concepts. For example, the management of properties is primarily concerned with boundary lines and their exact positioning. Plot sizes (areas), boundary courses (lines) and boundary stones (points) play an important role, so that the geometric accuracy of the data and the cartographic representation are particularly important. In network information systems, on the other hand, supply or disposal networks for gas, water or electricity, for example, are mapped. A pipeline is represented in the system by a line, but requires additional information such as the (flow) direction, the flow rate or the branching at intersections.

Illustration 2.4.1: Different end devices for GIS applications (Source: https://www.topographics.de/gis-anwendungen/gis-applikationen/esri-gis/). |

|

Interactive mapsCartographic representations are now a common source of information on many websites. Whether for tourist destinations, company presentations or the websites of municipalities and cities, geoinformation is always present and positioned in central locations due to its high level of visualisation. Whereas in the past most map representations were static and could only be viewed but not changed by the user, today's maps are mostly interactive. This allows the user to determine or retrieve the information content and the wealth of information. The features of interactive maps include functions such as zoom, location search, moving the map section, clickable elements, calling up information, changing colours and symbols or showing and hiding information layers (e.g. weather data, hiking trails, roads, tourist attractions, buildings and much more). Interactive map services are offered by many companies today (e.g. Google, Microsoft, Yahoo, ...). Google Maps is probably the best-known information portal. In addition to the interactive functions already mentioned, it now offers a wide range of applications. For example, you can switch between a map view and a satellite view (aerial view) or even display an intersection of both (hybrid). Another frequently used function of Google Maps is the calculation of driving routes. By defining a starting point and destination based on address data, information on optimum routes can be called up. The result is presented both on the map and in a textual explanation with navigation instructions. Alternative routes are also suggested, which may differ in terms of distance or journey time. The route can be shifted as required by simply clicking on the calculated route in the map display. The system constantly updates the information on route length and time. The quality of the information depends on the available geodata, in particular the road network, and the algorithms used to determine the route. In order to obtain meaningful information, the database must contain information such as whether the road is a one-way street, how fast I am allowed to drive on it or whether the road is open to traffic at all. As the road network can also change, the geoinformation must always be kept up to date. Recently, attempts have even been made to include real-time traffic jam and accident information in the calculation of time-optimised routes. The market for geodata and geoinformation systems was revolutionised by developments in the field of interactive maps and virtual globes. Although the software solutions had been available since the 1970s, albeit not in the quality we know today, it was mainly due to the lack of geodata or the very high costs associated with its availability. So what is a geoinformation system without data? It was not until the widespread introduction of freely accessible geoinformation services by Google and other large Internet and software companies, for example, that the way geoinformation was handled changed. Since then, digital geodata such as road networks, national borders or satellite images, which were previously only available to the military, authorities or wealthy users, can now be viewed. Competition between the various systems and competition between commercial providers and state or official map services has led to a rapid expansion of geodata, which continues to this day. As a result, there are now completely new possibilities for using geoinformation systems. Interactive maps and interactive cartographic applications predominate on the Internet. They allow statistics in particular to be visualised very quickly and conveniently in cartographic form and presented to a wide audience. In contrast to a comprehensive GIS, however, no new data can be integrated, but only views and functions specified by the author can be used. As a result, although they are interactively presented systems, they are closed in terms of the data they contain and are therefore spatial information systems.6 Web-GISWeb GIS applications are similar at first glance due to their presence on the Internet - in the true sense, they are a website or web application - but the difference is significant. For example, web-based GIS allow a much wider range of functions, giving the user the opportunity to compile their map individually from existing data (maps on demand), to freely select the section (zoom) and to carry out simple analysis steps (e.g. data query and measurement). In some cases, it is even possible or desirable to integrate your own data into the system and thus change the database. Due to their intuitive design, users of such web services generally do not need any special GIS knowledge, but only need to be familiar with the use of Internet browsers and with navigating or orientating themselves in maps and reading map information. Web applications for planning outdoor activities such as cycling, mountain biking or hiking make particular use of this technology. Users can create their own routes on their PC and download them as GPS tracks, for example. But statistical offices and public administrations also use such applications to provide citizens with comprehensive information.7 Desktop GISIn contrast to interactive maps and web GIS, desktop GIS offer numerous analysis tools, improved data management and unrestricted access to the geodata stock (manipulation), which is why they are only now being referred to as comprehensive GIS in the sense of the above definition. The structure of the software is modular and is often divided into three subsystems: The data management and organisation, the analysis and query, and the presentation interface. Each subsystem provides special functions for capturing, storing, checking, manipulating, integrating, analysing and displaying data. In practical use, the quality of desktop GIS offerings is usually defined by the scope of analysis tools and their quality. This shows that open source products (e.g. QuantumGIS, gvSIG or GRASS GIS) sometimes lag behind paid software solutions (ArcGIS or Map3D), but have experienced a steady expansion of functions in recent years.8 Mobile GIS

Similar to other web-based applications, the trend in GIS is also moving towards mobile devices on the one hand and centralised systems on the other. Applications for mobile phones or tablet PCs with map displays or spatial information platforms (e.g. route planning) are no longer a rarity and are increasingly conquering everyday life. At the same time, special spatial analysis functions are provided via central GIS servers (GIS application servers). However, data can also be stored and delivered on request (e.g. geodatabase server) or made available for a website or web application (web GIS server). In addition to simply calculating routes on the internet, mobile navigation has become an integral part of many people's everyday lives. Numerous mobile devices such as smartphones or car navigation devices offer help in finding locations in conjunction with global satellite positioning services (GNSS, Global Navigation Satellite Systems). However, there is more to navigation software, whether on the Internet or in mobile devices, than just displaying maps on a screen. How can networks be captured and correctly mapped both cartographically and topologically? Which algorithms are best suited for calculating routes? In addition to the pure search for an optimised route, as already shown in the example of Google Maps, position determination is an indispensable component of navigation with mobile devices.

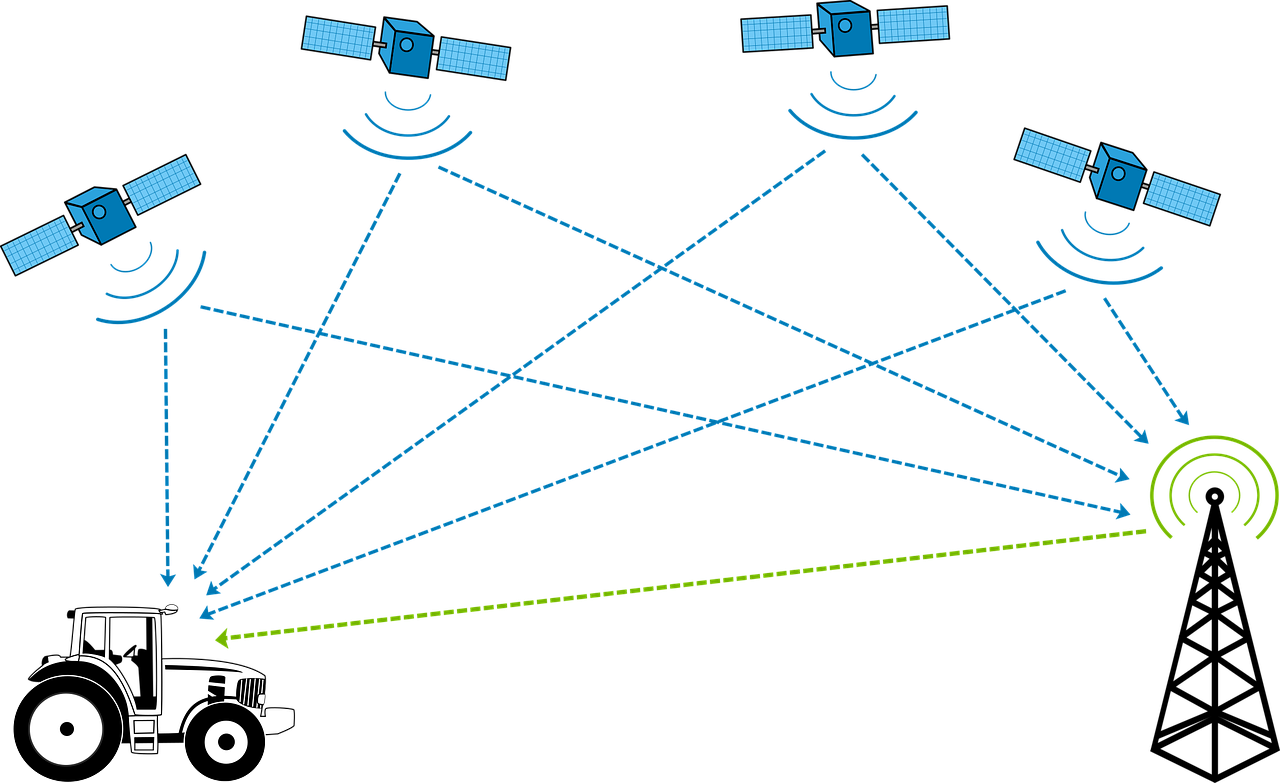

Illustration 2.4.2: Positioning with the help of satellites. The devices utilise the satellite positioning available worldwide. The best-known of these is the American Global Positioning System (GPS) or NAVSTAR GPS. This originally military satellite system has only been available for civilian applications, such as vehicle navigation, for around fifteen years. With an accuracy of approx. 3 to 5 metres, the GPS signal can be used to determine your own position on the earth. Constant positioning even makes it possible to measure the direction of movement and speed.9 Satellite positioning is important for many geoinformatics applications and influences our daily lives: you can see satnavs in many cars, almost every modern smartphone has a GPS function and GPS is also increasingly being integrated into many notebooks and tablet PCs. But this is not the end of the story. With the European Galileo system, the Russian GLONASS and the Chinese Compass system, there are promising competitors for GPS. For a more in-depth look at the topic of global positioning systems, please refer to the in-depth chapter "Global Navigation Satellite Systems". Virtual globesFrom the point of view of geoinformatics, this is a logical development, and for the general public it is a fascinating tool: the introduction of so-called Earth Viewers. Google Earth, Marble, Microsoft Bing Maps 3D and NASA World Wind are just a small selection of the many programmes that make it possible to view spatial data and satellite images on a digital globe. Virtual globes are also geoinformation systems that provide information about spatial structures and processes. The technical challenge here is the three-dimensional presentation of the data on a globe that can usually be freely rotated and zoomed, as well as the transmission (streaming) of large volumes of geodata. Virtual globes usually use aerial and satellite images as a (cartographic) basis, which are accurately projected onto the earth's surface and onto a digital terrain model (DTM) (image draping). This creates the impression of a three-dimensional photorealistic view with an oblique aerial view (see Figure 9). In addition to the satellite images, further geoinformation such as streets, towns or so-called points of interest (POIs) can be displayed. Virtual globes also make it possible to integrate your own data, such as photographs or POIs, into the system. Other functions include visualising the course of the sun with shadow formation, historical aerial and satellite images or viewing three-dimensional animated buildings or entire cities.

Illustration 2.4.3: Screenshot Google Earth. Current efforts are focussed on the integration of real-time information or near-real-time information such as cloud distribution or weather conditions and the collection of further geoinformation. The latter includes the systematic recording of entire streets and cities with digital image material using 360° ground views (panoramic images). Virtual globes are increasingly being supplemented with this information in order to offer the user a zoom to the ground perspective. This allows the situation on site to be viewed from a simulated perspective. With their fascinating functions, virtual globes have become as much a part of everyday life as GPS or route planning. e.g, television news programmes are increasingly using virtual globes to present the region of the news item in question or tourists to visit their holiday destination virtually before starting their trip. However, technological development continues. New geodata of ever-improving quality is being recorded and its visualisation, it also improved on mobile devices. The technology is also being transferred to other planets and celestial bodies, so that Google can also offers a three-dimensional view of the moon or Mars. |

|

Comprehensive work with GIS today requires a combination of the aforementioned applications and options. For example, geodata is managed centrally on a server, which requires appropriate database management. Users access this data via the Internet, geospecialists analyse and process the data in desktop GIS and web applications make the information available to a wide audience and enable it to be used on mobile devices. The wide range of GIS applications demonstrates the great relevance of spatial information, as all the applications mentioned are ultimately about creating a link between space and information. |